NIMHD Insights 2024

NIMHD Insights features posts by NIMHD leaders, researchers and staff, and guest contributors, focused on multidisciplinary research, resources, and the people working to advance minority health and eliminate health disparities.

NIMHD Insights features posts by NIMHD leaders, researchers and staff, and guest contributors, focused on multidisciplinary research, resources, and the people working to advance minority health and eliminate health disparities.

-

Breaking Barriers: Empowering Black Young Adults to Embrace COVID-19 Vaccination

By Lisa Hightow-Weidman, M.D., M.P.H., and Henna Budhwani, Ph.D., M.P.H.

Florida State University (FSU) College of Nursing

Posted Aug. 15, 2024 The COVID-19 pandemic was a frightening and uncertain time. Schools closed, office work went virtual, and countries shut their borders. In the early days of the pandemic, hospitals were overrun, and over six million people died; of our fallen, 13% were African American or Black. In 2020, the largest increase in deaths was among American Indian and Alaska Native (36.7%) and Black (29.7%) populations. Collectively, we held our breath, waiting for a scientific miracle.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a frightening and uncertain time. Schools closed, office work went virtual, and countries shut their borders. In the early days of the pandemic, hospitals were overrun, and over six million people died; of our fallen, 13% were African American or Black. In 2020, the largest increase in deaths was among American Indian and Alaska Native (36.7%) and Black (29.7%) populations. Collectively, we held our breath, waiting for a scientific miracle.To respond to this global threat, an internationally coordinated effort was made to develop an effective COVID-19 vaccine. In 2020, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued emergency use authorizations (EUA) for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and the Moderna vaccine. Both vaccines were mRNA-based. In 2021, the FDA issued an EUA for the Jassen vaccine, which leveraged the adenovirus vector. Historically, the vaccine development process takes about 11 years; thus, the expeditious release of three COVID-19 vaccines built using two different technologies caused skepticism, fueling hesitancy and an unwillingness to accept the vaccine.

Understanding the Assignment

Even before the approval of COVID-19 vaccines, misinformation and false narratives about them flooded social media, leading to widespread hesitancy. Black young adults, especially those in the southern United States, were particularly hesitant, with early estimates showing only 42% were likely to accept the vaccine. This skepticism and rampant misinformation, coupled with systemic health care barriers that harm Black populations, made it imperative to find effective ways to reach and engage Black young adults living in southern states expeditiously.

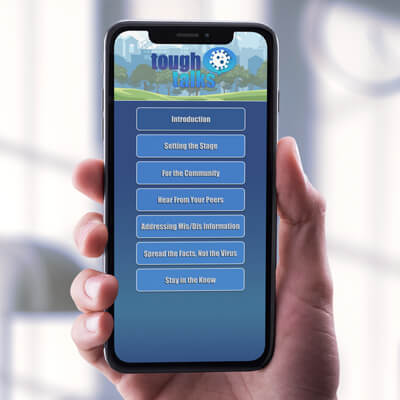

A screenshot from the Tough Talks COVID-19 mobile application. Credit: Virtually Better, Inc

A screenshot from the Tough Talks COVID-19 mobile application. Credit: Virtually Better, IncThe National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), as the young people would say, understood the assignment. They released a funding announcement to promote the COVID-19 vaccine to minority populations. We saw this opportunity and knew we had to respond with all we had. Bet! We live in the southern United States, and this was our chance to contribute to the well-being of our communities. We knew time was of the essence, so we developed a proposal to adapt the “Tough Talks” digital health intervention that engaged young adults to promote HIV-related health into Tough Talks for COVID-19 or TT-C.

The Tough Talks for COVID-19 Intervention Study

To build trust, we had to be innovative in our approaches while also being completely real about the quickly changing landscape of COVID-19. And so, we pulled together a team of diverse scholars and community partners to inform the entire project. We took guidance and direction from experts: both leaders at minority-serving institutions and Black young adults living in southern states. We listened, we learned, and then we created the TT-C digital health interventions featuring:

- Testaments: Black young adults living in southern states shared their personal experiences and reasons for getting vaccinated via real-world video-based digital stories.

- Interactive Activities: We included choose-your-own-adventure games and engaging activities that explained complex biomedical concepts in relatable, youth-friendly ways.

- Non-Stigmatizing Messaging: Collaborating with our advisors, we crafted tailored, non-judgmental, and supportive messages that addressed common misconceptions and fears without alienating participants.

- Educational Content: We embedded comprehensive information about COVID-19 vaccines, including their safety and efficacy, and general preventative health tips, like proper handwashing techniques.

To evaluate the TT-C intervention, we conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) with 360 Black young adults aged 18-29 from Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina who were unvaccinated or not fully vaccinated per current recommendations. Participants were recruited via social media. Once enrolled, participants were randomly assigned to either the TT-C or the control group. Self-reported data on vaccination and related constructs were collected at multiple points through 3-months post-randomization. Our primary outcome was COVID-19 vaccine uptake, verified by vaccine cards and survey responses. Secondary outcomes included measures of vaccine hesitancy, confidence, knowledge, and conspiracy beliefs. We tracked paradata to assess intervention engagement and were 100% accessible to our participants and partners.

Vaccine Interventions are Game-Changers

Preliminary observations suggest that TT-C holds significant promise. By using digital storytelling and incorporating valuable insights from young adults and expert advisor boards, TT-C resonated with Black young adults. The mobile app format ensured that participants could access information and support from anywhere using a youth-friendly modality, removing barriers like transportation and the need for clinic visits. The intervention’s culturally relevant content addressed concerns and misconceptions unique to the community’s lived experiences, fostering trust and confidence.

Vaccination saves lives; specifically, since the 1970s, vaccination has saved 154 million lives globally. If TT-C is indeed successful at reducing vaccine hesitancy and improving vaccine knowledge, there will be a strong case for adapting TT-C to promote other vaccines like influenza and HPV to avert preventable diseases, such as cervical cancer. By breaking down structural barriers and giving those we aim to support a true voice in the scientific process, we can foster trust, fight misinformation, and reduce vaccine hesitancy. Together, hand in hand, we can create a healthier future by improving rates of life-saving vaccinations.

Learn More

For more information on this project, visit our website and follow us on social media for updates on TT-C and our other health equity initiatives and success stories.

Lisa Hightow-Weidman, M.D., M.P.H., and Henna Budhwani, Ph.D., M.P.H., are co-principal investigators of the Tough Talks for COVID-19 study.

Dr. Hightow-Weidman is a Distinguished and Endowed McKenzie Professor at the Florida State University (FSU) College of Nursing. She is the founding director of the Institute on Digital Health and Innovation and the contact PI of the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Intervention (ATN) Scientific Leadership Center.

Dr. Budhwani is a professor at the FSU College of Nursing and leads the Institute on Digital Health and Innovation’s Intervention Research and Implementation Science Hub. A medical sociologist by training, Dr. Budhwani’s research focuses on addressing health inequities among adolescents and young adults via pragmatic clinical trials.

-

African American Faith Communities: Foundations for Mental Wellness

By Rebecca Selove, Ph.D., M.P.H.

With contributors Rev. Neely Williams and Rev. Dr. Omaràn D. Lee

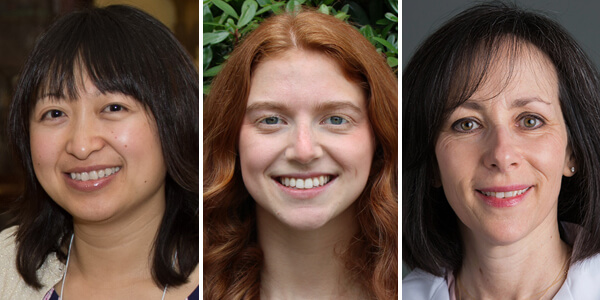

Posted July 31, 2024 Left to right, Dr. Rebecca Selove, Rev. Neely Williams, Rev. Dr. Omaràn D. Lee

Left to right, Dr. Rebecca Selove, Rev. Neely Williams, Rev. Dr. Omaràn D. LeeThe role of the church in African Americans’ lives and communities is immense and multi-faceted. In his recent book, The Black Church, Henry Louis Gates wrote, “The Black Church was the cultural cauldron that Black people created to combat a system designed in every way to crush their spirit. Collectively and with enormous effort, they refused to allow that to happen.”

A 2021 survey indicates that 47% of Black Americans attend church at least once a week, more than any other racial and ethnic group, and more than half of Black Americans who participate in church activities attend congregations that they identify as a Black church. These powerful and potent community centers’ historical and social roles align with NIMHD’s mission to improve minority health and reduce health disparities. They are addressing mental health needs as part of their dedication to supporting the health of their community’s soul. Researchers who focus on addressing African American health must engage leaders of these congregations as teachers and mentors for their research endeavors. These leaders already know much of what scientists want to understand.

Sabbath services in Black churches are often joyful expressions of gratitude and support. Messages from the pulpit and choir that acknowledge challenges, such as physical suffering, financial stress, grief, and anxiety, are offered in the overarching context of appreciation for the support, power, and goodness of God.

As someone of European Jewish ancestry, my education about Black churches began fairly recently. I am a member of the research team for the NIMHD’s Engaging Partners in Caring Communities (EPICC) project designed to build the capacity of congregations that serve African American communities to implement health promotion programs. I have enjoyed being welcomed into uplifting and inspiring Sunday morning services with our partners. “Good morning, Church” is a frequent greeting to all who are gathered in the sanctuary – everyone is included in the loving welcome.

At the same time that I have been experiencing the joy and warmth of the African American faith community, my faith leader partners and teachers in the EPICC project have been sharing their concerns about mental health issues affecting many in the African American community. They tell me about being called to address high levels of suffering associated with bereavement, suicide, substance use disorders, anxiety, depression, and youth and family violence. Pastors feel responsible for addressing these concerns while being very aware that the larger community offers inadequate support and resources that are sensitive to the needs and culture of African Americans. They note disparities in mortality associated with COVID-19 in African American communities, anxiety about access to trustworthy healthcare, and isolation associated with virtual participation in church activities during the pandemic.

The research literature reflects their leadership in health equity, social justice activism, and community-academic partnerships emerging to build on the long-standing strengths and mission of faith communities. Pastoral care and church-based programs to address depression and alcohol use disorders, and to reduce mental health stigma are examples.

At a recent gathering of leaders from nine EPICC partner congregations, Ms. Gwen Hamer from the Tennessee Department of Health and Mr. Sheldon Walker of Davidson County Metro Health Department described the Suicide Prevention and the African American Faith Communities Coalition (SPAAFCC), which started in 2009. Gwen told us, “… leaders in the African American faith communities… are one of the first people to be contacted when one of their parishioners is contemplating suicide or if a family member or friend of someone who has died by suicide needs comfort and encouragement. We felt their input in developing strategies to raise suicide prevention awareness and to help save lives from suicide in their faith communities was absolutely vital.”

SPAAFC provides monthly virtual meetings for members to support one another, as well as training in programs such as Question, Persuade, and Refer also known as the QPR Gatekeeper Training.

Our EPICC project team benefits from the guidance of two leaders in the Nashville African American faith community. Rev. Neely Williams has a long history of community advocacy and collaboration with academic researchers. Rev. Williams counsels our EPICC research staff to listen for our faith community partners’ strengths and to acknowledge the insights and priorities of church leaders. Rev. Dr. Omaràn D. Lee, a pastor and mental health practitioner currently serving as regional director of the Tennessee Governor’s Faith-Based and Community Initiative, helped develop the EPICC proposal. He leads programs through the Reach One, Teach One Foundation and Centers for Well-Being to support pastors and faith leaders so they can better serve their congregations.

Faith community leaders have been providing a foundation for mental wellness for centuries, building on the considerable strength and wisdom of their spiritual traditions, their response to being called to serve their congregations, and their deep compassion for fellow human beings. We are grateful to be invited to join them in this effort.

Rebecca Selove, Ph.D., M.P.H., is director of the Center for Prevention Research at Tennessee State University. She has served as a clinical psychologist in a variety of community settings and is currently focusing on implementation science and community-engaged research to promote health equity.

Rev. Neely Williams is a minister, a community advocate, and a community organizer who has actively participated in the work of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) since its inception over 10 years ago. She serves as a consultant to the EPICC project’s research and community partner staff, lifting and articulating the community perspective on health disparities and health equity.

Rev. Dr. Omaràn Lee, formerly the director of the Congregational Health Network (CHN), helped develop the funding proposal for EPICC. He is a pastor, a pastoral counselor, and regional director of the Tennessee Governor’s Faith-Based and Community Initiative, where he oversees the collaboration and coordination of faith-based and community organizations to address social issues and improve the quality of life for Tennesseans.

-

Can Virtual Reality-Based Stress Reduction Interventions Be a Game Changer for Addressing Intersectional Stress Among Minoritized Women?

By Judite Blanc, Ph.D.

University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

Posted July 22, 2024

My journey to the field of stress research and disaster mental health began during my postpartum as a first-time mother, after surviving the most devastating Haiti earthquake in 2010, which claimed over 200,000 lives. Worried about our safety and too scared to hide under my bed, halfway through my master’s degree in developmental psychology at the time, I grabbed my baby and hurried into a closet. As the place was shaking and my baby was screaming, I thought we were going to die alone. We were not injured, but with each aftershock, I was terrified that our house would collapse on us.

After the earthquake, similarly to thousands of displaced survivors, we left Haiti for a month or two and went to Florida for safety, but I knew my place was in Haiti. So, in March 2010, I returned and joined Haiti’s Psycho Trauma Center, which was set up to help heal survivors’ psychological wounds.

I enjoyed working with the displaced children. Nevertheless, I was also curious about the efficacy and cultural limitations of these Western-centered theoretical frameworks that inspired our interventions. I obtained a scholarship to complete my graduate studies in the field of psychopathology and health psychology in France, where I received extensive training in traumatic stress research. Findings from my dissertation project highlighted the urgent need for trauma-focused and holistic programs for perinatal women, mother-children dyads, and school-aged children who are survivors of traumatic events.

A few years after the disaster, I moved to the United States. I was confronted with another traumatic reality: Black women and their children, regardless of education levels, suffer significantly from health disparities. For instance, they are the most affected by the maternal mortality crisis in the U.S., which is comparable to that of lower-middle-income countries, making it a national public health emergency. This realization further fueled my passion for addressing these disparities.

Evaluating the Effect of a Virtual Reality Program on Maternal Stress Among Perinatal Women of Color

Perinatal mental health issues are the drivers of complications during pregnancy, childbirth, and maternal mortality. Studies indicate that 15% to 20% of pregnant and postpartum individuals in the U.S. suffer from mood or anxiety disorders. However, this mental health crisis does not affect all racial and ethnic groups equally. Women, particularly Black women from marginalized communities, are disproportionately impacted, underscoring the complex interplay of race, ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status.

A mom uses the NurtureVR headset and controller in her hospital room to relax and learn.

A mom uses the NurtureVR headset and controller in her hospital room to relax and learn.In response to this crisis, in 2022, The Media and Innovation Lab and I implemented the ongoing Nurturing Moms study at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Our study assesses Nurture VR™, a virtual reality (VR)-based, pregnancy-related education program integrating mindfulness techniques, relaxation exercises, and guided imagery for perinatal Black and Latina women. VR uses computer modeling and simulation to allow a person to interact with a simulated 3D visual or sensory environment.

In our recent qualitative phase of the study, we learned about specific challenges faced by our volunteers, such as time management difficulties, caregiver burden, financial strain, insufficient sleep, societal pressures, lack of social support, traumatic stress, and inadequate health care coverage.

While conducting the focus groups, I was struck by the contrasting perspectives among participants. Some Latina women emphasized the inherent resilience of motherhood, while Black participants expressed frustration with the societal expectation of the "strong Black woman" archetype.

"The idea that you just got to keep pushing forward even if the day is tough, like you have to. You’re a mom. You got to like suck it up and do dues because these kids need you, and then at the end of the day, when you want to unwind and go to bed, you end up scrolling through your phone because that’s your only me time."

– Expectant mother of one, Hispanic"Everywhere as a Black woman, you have to be strong, and I just can’t stand to hear that because it’s like, why are we the only race that have to be strong? Why everybody else gets to cry, get to show emotion, get to feel, but we always have to be strong."

– Expectant mother, Haitian-bornThe women’s responses highlight the nuanced experiences within different cultural contexts. Additionally, there were varied views on the new medicine for postpartum depression, zuranolone. Some participants said they favor complementary medicine, and others showed strong interest in it due to limited access to mental health professionals.

Many of our study participants provided positive feedback, emphasizing that the immersive quality of VR effectively engaged them and demonstrated its effectiveness in creating a unique experience through guided imagery and relaxation techniques. For example, while wearing the VR headset, pregnant or new moms can select educational modules or guided imagery that allow them to become entranced by the rhythmic waves of a beach or the tranquility of a green space. This experience can elevate their mood and help them focus, learn, and retain positive experiences.

A prominent theme that emerged was the participants’ sense of escapism. The portability and on-demand nature of VR-based interventions make them a valuable asset for low-income communities. In these communities, transportation challenges, cultural barriers, and the stigma surrounding mental health can significantly hinder access to quality mental health services among marginalized populations.

Culturally tailored and affordable VR-based interventions have the potential to mitigate these barriers, thereby contributing to the reduction of social determinants of health stressors among women and mothers of color.

Judite Blanc, Ph.D., is a 2023 NIMHD HDRI Scholar and a multilingual assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Dr. Blanc leverages innovative ethnographical and integrative medicine tools to investigate and confront cumulative intersectional stressors. Her work evaluates the stress responses among marginalized families, women, and children to provide solutions for transforming the lives of families, women, and children through science, education/training, community services, and advocacy in the United States and globally. She was recently awarded a K01 from NHLBI to evaluate a Virtual Reality Intervention for Stress, Resilience, and Blood Pressure Management in Black Women (1K01HL175286-01).

-

Optimizing Health for Immigrant Populations: When One Thing Stands, Another Thing Stands Beside It

By Yewande Oladeinde, Ph.D.

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

Posted June 10, 2024 Most immigrants have frames of reference or ways of knowing based on their immigrant experience that confer certain health advantages in positive and unique ways, often known as the “healthy immigrant effect” or the “immigrant paradox.” To better understand the rationale behind why and how immigrants seek care, we need to know “what are those things that stand and what are the other things that stand beside them," as immigrants try to navigate a fragmented health care system that was not built for them.

Most immigrants have frames of reference or ways of knowing based on their immigrant experience that confer certain health advantages in positive and unique ways, often known as the “healthy immigrant effect” or the “immigrant paradox.” To better understand the rationale behind why and how immigrants seek care, we need to know “what are those things that stand and what are the other things that stand beside them," as immigrants try to navigate a fragmented health care system that was not built for them.The quote referenced above by Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe refers to the "reality of a cultural multiverse rather than a cultural universe." As public health professionals, we often think about developing and implementing sustainable interventions that will lead to improved health outcomes. As noble as this may sound, many public health professionals design interventions that fail to consider the cultural contexts within which the behaviors and practices they are trying to change are formed and from which they thrive. Failure to do so leads to interventions that are unsustainable at best and, at worst, ineffective.

Dr. Yewande Oladeinde wearing traditional Nigerian gele head wrap made with aso-oke fabric and dress made with ankara fabric.

Dr. Yewande Oladeinde wearing traditional Nigerian gele head wrap made with aso-oke fabric and dress made with ankara fabric.Highlighting Cultural Assets

Immigrant Heritage Month is about celebrating diversity and one's cultural heritage. It’s also about highlighting the cultural assets people bring to their health that can then be used to develop programs that end disparities while optimizing health for all people.

Take the story of Kemi, for example, a first-generation immigrant woman rooted in the Yoruba culture of Nigeria and an American anchored in the African American experience. Kemi has lived in the United States for over two decades despite spending her formative years in her home country of Nigeria. To remain connected to her Nigerian roots, she and her family are active members of a cultural organization for Nigerians in her community. Even though Kemi has lived in the United States for over two decades, she is very much rooted in her Yoruba culture.

Kemi was experiencing symptoms of extreme fatigue, a feverish feeling, and other flu-like symptoms. At the time when she was experiencing these symptoms, she wanted to see a doctor, but she heard the news of how nobody was allowed to accompany loved ones to the hospital. People were asked to literally drop off their loved ones to an unknown fate and leave them there. Because of this rule, Kemi decided to stay home and have her loved ones care for her.

Kemi called her mother in Nigeria to inform her about her symptoms and to ask for the agbo, a Yoruba term for a medicinal herbal remedy that is commonly used for feverish conditions. Her mother gave her the names of the herbs she needed, the specified quantities, and the preparation instructions. Her husband tried to purchase the medicinal herbs recommended, but many of them were unavailable in the United States. Kemi’s mother shipped the agbo remedy from Nigeria. Kemi drank a 4- to 8-ounce cup of the medicinal herbs each day. After about two weeks, her symptoms abated.

Prior to this incident, Kemi used Western allopathic medicine often. However, when she was in a dire health situation, and some of the allopathic treatments recommended to her were not working, she knew she had to rely on “those other things that seek to stand beside that one thing,” such as traditional cultural practices and values related to healing that sustained prior generations, and reliance on the wisdom and divine power of one’s mother.

When Kemi’s friends spoke to her about possibly seeking care as her symptoms got serious, she stated, ”What is the point of going to the hospital and being subjected to trial-and-error treatment when I can rely on what mothers and grandmothers in my culture have used for several generations that worked for them?” She relied on her cultural identity and the value of what had worked for previous generations. This is one of the reasons why it is important to build and maintain trust with the medical community and between people from other racial and ethnic minority communities, as cultural factors may influence their perceptions of health and uptake of recommended guidelines of care.

As we continue to celebrate our diversity and cultural heritage this month, we must remember to:

- Pay attention to the perceptions that feed people’s beliefs and the broader contexts where these perceptions emerge and from which they thrive. People’s perceptions, be they sociocultural, political, or historical, do not emerge from a vacuum.

- Keep indigenous ways of knowing, which have helped our ancestors thrive. Chinua Achebe's quote speaks to the essence of multiple ways of knowing, which often coexist within an individual and may sometimes complement or oppose more popular views.

- Understand that there is no singular worldview or universal belief that resides within an individual, and trying to silence other narratives or beliefs would be detrimental to addressing pressing health challenges faced by immigrants in the United States.

- Encourage and empower alternate perspectives of people from other cultures, the things they value, and the unique qualities they acknowledge while leveraging their assets for optimal health.

Yewande Oladeinde, Ph.D., is a social and behavioral science administrator in the Division of Clinical and Health Services Research at NIMHD. Her research focuses on understanding the role culture plays in shaping people’s perceptions of health and illness, and how it influences their choices and their behaviors, with a goal of implementing culturally and contextually appropriate interventions. Dr. Oladeinde was born and raised in Lagos, Nigeria, and she is from the Yoruba ethnic group.

Dr. Oladeinde writes periodically for a local Maryland newspaper and aspects of this story were previously published there.

-

Confronting the Legacy of Medical Misinformation - Let's Start With Race-Based Medicine

By Keisha Bentley-Edwards, Ph.D., Olanrewaju Adisa, Kennedy Ruff, and Catherine Kiplagat

Samuel DuBois Cook Center Health Equity Working Group

Posted May 30, 2024

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the health community was alerted to the proliferation of medical misinformation, particularly messages related to vaccines and treatment. For me, Dr. Bentley-Edwards, I became alerted to the dangers of medical misinformation in the early 1990’s from my father’s annual physical. My father’s new primary care provider (PCP) asked him what medication he was taking to control his hypertension. My father was confused. He wasn’t taking antihypertensive medication because his blood pressure was normal. However, his medical records revealed his blood pressure was well above the hypertension level cut-offs for several years. In past years, my father’s prior doctors had been telling him that his blood pressure was “high-normal” or that his levels were “normal for a Black man.” This misinformation allowed his blood pressure to be uncontrolled for an unnecessarily long time, heightening his risk for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and kidney disease. Upon learning all of this, my father’s new PCP, a young Black doctor, immediately prescribed him the appropriate medication, and he has taken care of his health since then.

Loud and Wrong

Hypertension is often called the “silent killer,” but in this case, my father’s physicians’ reliance on race-based medicine to guide diagnosis and care rang loud and wrong. Race-based medicine relies upon biological distinctions between racial groups that are integrated into practice, training, and health algorithms and represents a systemic form of medical misinformation. As such, medical misinformation cannot be reduced to error-filled social media campaigns. As researchers, providers, and other members of the health community, we must reflect on how we generate, share, and sustain medical misinformation so that we can bring it to an end. To be clear, race-based medicine is not to be confused with personalized care or precision medicine.

Hypertension is often called the “silent killer,” but in this case, my father’s physicians’ reliance on race-based medicine to guide diagnosis and care rang loud and wrong. Race-based medicine relies upon biological distinctions between racial groups that are integrated into practice, training, and health algorithms and represents a systemic form of medical misinformation. As such, medical misinformation cannot be reduced to error-filled social media campaigns. As researchers, providers, and other members of the health community, we must reflect on how we generate, share, and sustain medical misinformation so that we can bring it to an end. To be clear, race-based medicine is not to be confused with personalized care or precision medicine.In the past, providers were taught to provide Black patients with a specific class of antihypertensive medication, narrowing their medication options early in their treatment course from those that may be more effective and reduce the risk for progression to chronic kidney disease. These race-based assumptions do not exist in a vacuum. They inform the development of critical assessments and risk predictors. This history calls into question the goal of algorithms to save time, money, or lives. If the goal of an algorithm is to save lives and reduce health disparities, an over-reliance on race-based medicine can get in the way of its success.

Important Steps

Prior to 2021, kidney function was determined by a calculation that considered multiple biological indicators and included a coefficient accounting for patient race. The use of this formula systematically overestimated kidney function for Black patients, reduced the chances of patients meeting the threshold for end-stage kidney disease, and increased the wait times for Black patients to get on the transplant list or receive other appropriate care such as dialysis. However, the National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology revised the eGFR recommendations to exclude Black race as a biological factor. In 2023, researchers estimated that roughly 70,000 Black adults could move higher up in the matching system and decrease their wait time for a kidney transplant as a result of the improved algorithm. As evidenced by the pre-2021 eGFR recommendations and the lack of evidence supporting race-based antihypertensive treatment, race-based medicine is not the solution. The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network took an important step to push policy that has helped nearly 2,500 Black patients receive a kidney who would not have if the old algorithm were still in use. More needs to be done to improve the health of Black Americans.

Race vs. Genetic Ancestry

Eliminating confusion by understanding race versus genetic ancestry is fundamental to addressing and redressing health inequities. Although structural racism is the most undeniable factor of disparate outcomes for Black patients with hypertension and kidney disease, ancestral genetic variation can partially explain differential experiences with kidney disease. APOL1 is a genetic marker present in all people; however, certain Black Americans (up to 10-15%) inherited a genetic high-risk allele combination (G1 and G2) that has evolved over 10,000 years beyond the original function in protection against African sleeping sickness (trypanosomiasis). This combination correlates with an increased risk of kidney diseases like kidney failure. Similar to sickle cell disease, there is an increased incidence of these alleles where the disease is prevalent (e.g., West Africa). APOL1-mediated kidney disease (AMKD) may accelerate the progression to kidney failure, but it is not the single cause of progression. Even with the help of ancestry studies, physicians must resist jumping to conclusions about how to use these findings to serve their patients.

Thoughtful Engagement

Studies about AMKD hold promise for personalized and genetically informed care for millions of Americans in the wake of precision medicine. Up against an extensive history of medical untrustworthiness by the U.S. health care and research systems, my team and I have argued that we must thoughtfully engage and include communities impacted by health disparities throughout the research enterprise.

Discussions of structural racism and medical misinformation do not diminish the relevance of personal agency and health behaviors. Yet, our personal agency is informed by the options that are available to us. When our choices are clouded by misinformation, so is our personal agency. Although I can’t decisively say that my father’s eventual progression to chronic kidney disease was the result of medical racism and structural racism, I can confidently say that it was contributing factor.

In the Health Equity Working Group for the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University, we study the causes and consequences of racism and sociocultural indicators on health outcomes. Does race matter in understanding health disparities? Yes, but we argue that when you recognize race as a social construct, you realize that social conditions should be an integral area of study for resolving racial health disparities. In our NIMHD-funded project, we examined Black people’s religiosity for its effect on cardiovascular disease risk factors, including hypertension. Our findings showed that Black religious and cultural experiences in America are diverse and important in understanding cardiovascular disease risks. Additionally, we are members of the recently formed ERASE-KD consortium (Eliminating Racism And Structural inEquities in Kidney Disease) dedicated to mitigating structural racism’s impact on kidney disease.

We, as members of the health community, must have the humility to recognize that we are not immune to the allure of medical misinformation, even when it is rooted in systemic racism. How this form of racism is reproduced and disseminated as medical misinformation is neither isolated nor benign.

Keisha Bentley-Edwards, Ph.D., is an associate professor of medicine, Co-Director of the Center for Equity in Research, and associate director of research for the Samuel DuBois Cook Center (Cook Center) on Social Equity at Duke University.

Olanrewaju Adisa is a medical student at Duke University.

Kennedy Ruff is an associate in research at the Cook Center and graduate student at North Carolina State University’s Clinical Mental Health Counseling Program.

Catherine Kiplagat is a 2nd year undergraduate student at Duke University.

Dr. Bentley-Edwards leads the Cook Center’s Health Equity Working Group, and Adisa, Ruff, and Kiplagat are all members.

-

Be the Source for Better Health

By CAPT Tarsha Cavanaugh, Ph.D., M.S.W., LGSW

Office of Minority Health

Posted April 26, 2024

We are nearing the end of National Minority Health Month (NMHM), an annual observance led by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Minority Health (OMH). NMHM is a time for us all to reflect on the role we can play in advancing health equity and eliminating health disparities in racial and ethnic minority and American Indian/Alaska Native populations.

This year the theme Be the Source for Better Health: Improving Health Outcomes Through Our Cultures, Communities, and Connections, emphasizes the role social determinants of health (SDOH), cultural competency, and humility play in advancing health equity.

At OMH we are committed to furthering this effort by providing resources that support federal and community-based partners’ provision of quality, equitable, and respectful care and services that acknowledge the diverse cultural beliefs, practices, and linguistic preferences among the populations we serve.

But let’s talk more about what health disparities are and how you can Be the Source for Better Health in your community.

Understand Health Disparities

Health disparities among minority communities are persistent and multifaceted. We define them as “differences in health that are closely linked to the social determinants of health (SDOH).” SDOH are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.

Health disparities among minority communities are persistent and multifaceted. We define them as “differences in health that are closely linked to the social determinants of health (SDOH).” SDOH are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.One of the many ways OMH works to address these disparities is through the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care. The Standards are a roadmap for improving the quality of care by providing equitable, understandable, and respectful care and services that pay keen attention to diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and communication styles.

By tailoring services to an individual's cultural and language preferences, you can help bring about positive health outcomes for diverse populations.

Be a Wellness Champion

Wellness Champions are federal and community partners committed to addressing the root causes of health disparities while advancing holistic approaches to achieve optimal health within racial and ethnic minority and American Indian/Alaska Native communities. Through education, outreach, and policy advocacy, they serve as trusted messengers empowering individuals to take charge of their health and navigate healthcare systems effectively.

Wellness Champions are federal and community partners committed to addressing the root causes of health disparities while advancing holistic approaches to achieve optimal health within racial and ethnic minority and American Indian/Alaska Native communities. Through education, outreach, and policy advocacy, they serve as trusted messengers empowering individuals to take charge of their health and navigate healthcare systems effectively.One type of Wellness Champion OMH supports is Community Health Workers (CHWs). CHWs often live within the communities they serve and broaden community connections to valuable health resources. They advocate for specific population needs (i.e., housing, food security), coordinate care at all levels, provide basic health screenings, and much more.

While CHWs are a great example of Wellness Champions, it is important to remember that anyone can be a Wellness Champion committed to promoting good health habits with your friends, family, and local community.

Embrace Self-Care and Self-Compassion

Encouraging self-care and self-compassion in both the populations we serve but also for ourselves is also an important element of achieving health equity. But equally as important is understanding that we all have unique health needs when it comes to these practices. Each person’s ‘healthiest self’ is different and influenced by SDOH.

Take the time to reflect on your personal wellness in areas such as your lived environment, relationships, and emotional health. Utilize resources like the NIH Your Healthiest Self: Wellness Toolkits to embrace self-care while navigating your whole-health journey and encourage others to do the same. Better understanding the knowledge gaps in our own health empowers us to seek out resources or trusted partners that can help improve our health status.

Take the time to reflect on your personal wellness in areas such as your lived environment, relationships, and emotional health. Utilize resources like the NIH Your Healthiest Self: Wellness Toolkits to embrace self-care while navigating your whole-health journey and encourage others to do the same. Better understanding the knowledge gaps in our own health empowers us to seek out resources or trusted partners that can help improve our health status.Embracing self-care or compassion practices, through activities such as mindfulness, exercise, or creative expression has the potential to nurture resilience and improve your well-being.

Conclusion

National Minority Health Month calls upon us to recognize the intersecting factors that contribute to poor health outcomes and work to overcome these barriers. When all receive quality, equitable, and respectful care and services that are responsive to our cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, economic and environmental circumstances, and health literacy levels, the health and well-being of our families, communities and nation will soar.

Let’s keep working together in NMHM and beyond to Be the Source for Better Health for populations we serve by advancing sustainable policies, programs, and practices that work towards eliminating health disparities and prioritize the achievement of health equity.

Resources

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030.

Office of Minority Health. National CLAS Standards. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Community Health Workers. U.S. Department of Labor.

National Institutes of Health. Your Healthiest Self: Wellness Toolkits. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

CAPT Tarsha Cavanaugh, Ph.D., M.S.W., LGSW, is Principal Deputy Director at the Office of Minority Health.

-

How ScHARe's Big Data Approach Can Yield Big Gains in SDOH Research

By Dr. Deborah Duran, Ph.D.

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD)

Posted April 22, 2024 Social determinants of health (SDOH) are critical aspects for advancing health equity and part of this year’s focus for National Minority Health Month. Recent decades have brought increased recognition that social determinants of health SDOH drive health disparities, exerting profound and potentially larger impacts than medical care on risk for obesity, heart disease, cancer, maternal and infant mortality, and overall life expectancy.

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are critical aspects for advancing health equity and part of this year’s focus for National Minority Health Month. Recent decades have brought increased recognition that social determinants of health SDOH drive health disparities, exerting profound and potentially larger impacts than medical care on risk for obesity, heart disease, cancer, maternal and infant mortality, and overall life expectancy.These impacts are reflected in grim statistics. A baby born today in Colorado’s Summit County can expect to live 87 years, while a baby born in South Dakota’s Oglala Lakota County can expect to live only to 66—a life expectancy the United States as a whole surpassed by 1950. Black women in the United States have nearly 3 times higher risk of dying while pregnant than White women. The rates of maternal mortality among all racial and ethnic groups in the United States are much higher than in other comparable developed nations.

Determining how to address SDOH impacts is no simple task. But research on SDOH has reached a major inflection point: advances in technology, data science, and artificial intelligence (AI) have unlocked new resources that can help researchers identify, understand, and mitigate negative SDOH impacts, as well as identify protective ones. These tools have the potential to transform health disparities and health outcomes research.

The Science Collaborative for Health disparities and Artificial intelligence bias Reduction (ScHARe), which is training thousands of researchers, is designed to make these tools widely accessible. ScHARe’s new centralized cloud computing research platform improves access to population science, including SDOH-related Big Data, and breaks down the data silos that impede efforts to understand and address health disparities.

SDOH Research Requires Big Data

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control define SDOH as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.” SDOH include the ability to access safe housing, convenient transportation, nutritious foods, and quality health care. We know SDOH exert profound impacts on health, quality of life, and vulnerability to disease, but understanding how they do so is far from straightforward, considering:

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control define SDOH as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.” SDOH include the ability to access safe housing, convenient transportation, nutritious foods, and quality health care. We know SDOH exert profound impacts on health, quality of life, and vulnerability to disease, but understanding how they do so is far from straightforward, considering:- SDOH effects can manifest over decades. Exposure to lead in childhood, for example, heightens the risk of developing dementia later in life. Exposure to violence in childhood can alter brain development and stress responses, with health effects that reverberate throughout a lifetime.

- The burden of SDOH that negatively impacts health is not always predictable. People vary in their underlying susceptibility to specific stressors and diseases; for example, the same stressor may lead to depression or anxiety in some people and not others.

- Complex interactions exist among SDOH. For example, children who experience childhood trauma but have strong sources of love and support may fare better than those who lack such support. A lack of education can limit employment opportunities and income.

To understand how SDOH affect health—how they intersect, when they exert the largest impacts, and through what behavioral and biological mechanisms—researchers need massive amounts of data about individuals’ lives and health over time.

Yet much of the data exist in silos. Government benefits and income data might reside in one database and health outcomes data in another. Researchers need the ability to access and link these large, disparate datasets. They also need access to data collected and analyzed for one study and never revisited. Moreover, data must be broadly accessible—currently, data is often inaccessible to women and other groups historically underrepresented in data science. Addressing these needs is the driving force behind ScHARe.

Why ScHARe Makes Me Optimistic

ScHARe hosts a growing collection of more than 200 health disparities, health outcomes, and population science datasets that researchers can access and analyze. These datasets include NIMHD-funded research to satisfy NIH’s new Data Management and Sharing policy. ScHARe also provides easy-to-use, off-the-shelf data science and cloud computing tools that enable researchers to link data and amplify the power, complexity, and nuance of their analyses.

Most importantly, ScHARe is diversifying data science. Although AI is an essential analysis and policy tool, AI-based algorithms can be biased by poor design and insufficient or biased training data. Diverse perspectives

are needed to detect and root out potential biases in these data. This means upskilling researchers and students traditionally underrepresented in data science through ScHARe’s monthly “Think-a-Thon” webinar series that provides hands-on training and opportunities for research.As you recognize National Minority Health Month this year, consider joining our rich and growing community of scholars transforming the study of SDOH. To learn more, sign up for the ScHARe listserv today.

Dr. Deborah Duran, Ph.D., is senior advisor of data science, data analytics, and data systems to the NIMHD director. She coordinates NIMHD’s efforts to obtain better minority representation in data science and addresses biases in emerging technologies.

-

Feed1st – A Model for Alleviating Hunger With Dignity

By Jie Zhao, Ph.D., B.M., Claire Fendrick, M.P.H., Stacy Tessler Lindau, M.D., M.A.P.P.

The University of Chicago

Posted March 29, 2024 Feed1st, an open-access food pantry available to patients and their families at the University of Chicago Medicine began in a chapel closet. It was an idea sparked in 2010 by the hospital's chaplain, Reverend Karen Hutt. Initially, the food made available to the community via Feed1st was sourced from the Greater Chicago Food Depository, and the pantry was managed by faculty, staff, and community volunteers.

Feed1st, an open-access food pantry available to patients and their families at the University of Chicago Medicine began in a chapel closet. It was an idea sparked in 2010 by the hospital's chaplain, Reverend Karen Hutt. Initially, the food made available to the community via Feed1st was sourced from the Greater Chicago Food Depository, and the pantry was managed by faculty, staff, and community volunteers.No Barriers to Food

Personal care items being stocked in a Feed1st open-access pantry.

Personal care items being stocked in a Feed1st open-access pantry.Food insecurity is among the most prevalent health-related social risk factors affecting the population served at UChicago Medicine. An early needs assessment found that 32% of families experienced food insecurity during their child's hospitalization. Today, Feed1st operates 11 clinically integrated sites across the adult, pediatric, inpatient, and outpatient areas of academic health system’s South Side medical campus, including nearly every floor of the children's hospital, as well as oncology, obstetrics/gynecology, primary care, trauma clinics, adult and pediatric emergency rooms, and a hospital retail cafeteria. The Feed1st pantry sites are fully self-serve and open 24/7/365. No eligibility criteria, registration, documentation, or prescription are needed to obtain food.

Signage that reads: "Food for Everyone" is prominent at each location and encourages people to take the food they need for themselves or others. This approach minimizes stigma and maximizes the dignity of people experiencing hunger. It also creates awareness of food insecurity in our community and inspires people to contribute.

Meeting Needs at Critical Times and Places

Early during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Feed1st team added five strategically located pantry sites to meet the fast-growing need for food support. One pantry was located in the main lobby of UChicago Medicine Comer Children’s Hospital where we were conducting the NIMHD-supported CommunityRx for Hunger study (read the study article on PubMed). This pantry quickly became one of the largest distribution sites for Feed1st.

Given long clinical shifts and the need for some staff to live in temporary housing to mitigate the risk of COVID-19 spread, the staff breakroom became another pantry site. Feed1st’s total food distribution during the pandemic was more than double that of the pre-pandemic period. By contrast, another hospital using a traditional eligibility-based approach reported a decline in food distribution during the same period.

Since 2010, Feed1st has distributed more than 173,000 pounds of non-perishable food, reaching an estimated 82,000 individuals. Beginning in 2016, employees across medical center departments created the UChicago Medicine Garden Committee. This group uses space on garage rooftops and other medical center grounds to grow fresh produce. Since 2020, we have collaborated with the Garden Committee to distribute more than 6,000 pounds of fresh produce.

UChicago Medicine's Garden Committee members harvesting fresh produce to distribute to patients via Feed1st pantries.

UChicago Medicine's Garden Committee members harvesting fresh produce to distribute to patients via Feed1st pantries.Today, the daily Feed1st operations, including keeping pantry sites stocked, are managed largely by a volunteer workforce, drawing on the Feed1st Medical Student Organization at the Pritzker School of Medicine and the Premedical Student Organization, both at the University of Chicago. The hospital volunteer program also deploys its workforce to support Feed1st and helps credential student volunteers.

Collaborations That Ensure Warm Hand-offs

Dr. Stacy Lindau, the principal investigator of the CommunityRx for Hunger study, leads bimonthly Feed1st social care teaching rounds. The teaching rounds are an interprofessional learning program that includes students, staff, partners, and guests seeking to support or replicate the program. As part of the teaching rounds, volunteers are in direct contact with faculty leaders and program management staff, and together, they visit and inspect all pantry sites. Teaching themes typically include:

- Social drivers of health and illness, especially food insecurity.

- Understanding stigma and maximizing dignity in healthcare.

- Quality assurance and improvement.

- Community engagement.

Dr. Stacy Lindau (bottom left) leading Feed1st's interprofessional teaching rounds with UChicago Medicine's students, staff and guests.

Dr. Stacy Lindau (bottom left) leading Feed1st's interprofessional teaching rounds with UChicago Medicine's students, staff and guests.At each pantry site, faculty members observe students as they introduce themselves to unit staff, provide brief education about Feed1st, and ask for ideas about how the program can better meet local needs. Students receive real-time feedback about their communication skills and ideate strategies for ongoing engagement and communication with local champions and partners.

A Feed1st pantry in the Sky Cafe (hospital retail cafeteria).

A Feed1st pantry in the Sky Cafe (hospital retail cafeteria).In October 2023, informed by findings from the ongoing CommunityRx for Hunger trial, Feed1st partnered with Aramark, the medical center's food service vendor, to launch a Round-Up program at three retail food sites. This program invites customers to "round up" their purchase to donate to Feed1st (e.g., a $5.95 purchase could be rounded to $6 to make a 5-cent contribution). To our knowledge, this is the first hospital-based food pantry to test a scalable and replicable philanthropic model for financial sustainability. We are currently studying the impact of this innovation.

The Feed1st program is both the focus of ongoing research and innovation, and it is critical to the success of our larger program of social care intervention research. Our team is currently conducting three NIH-funded social care trials. Feed1st enables an emergency source of food support to be available to study participants who identify as food insecure in the course of our research.

Feed1st Toolkit

Our free, downloadable Feed1st Toolkit can be used to help replicate and implement the Feed1st model. We regularly consult with hospitals and other healthcare organizations across the country who are inspired to open integrated food pantries utilizing an open-access approach. To our knowledge, at least three other hospitals have replicated some or all of the Feed1st model, including Johns Hopkins Children's Hospital (Baltimore, MD), Swedish Hospital (Chicago, IL), and Roseland Community Hospital (Chicago, IL).

Jie Zhao, Ph.D., B.M., is associate director of operations and the Feed1st manager.

Claire Fendrick, M.P.H., is Feed1st’s operations lead.

Stacy Tessler Lindau, M.D., M.A.P.P., is the Catherine Lindsay Dobson Professor of Ob/Gyn and Professor of Medicine-Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at the Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Chicago.

They work together at the Lindau Lab.

-

Moving From Willingness to Vaccination Uptake: Strategies for Promoting Health Through Vaccines

By Deborah E. Linares, Ph.D., M.A. and Vanessa Marshall, Ph.D.

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD)

Posted March 7, 2024 Moving from willingness (to take a vaccine) to vaccination uptake remains a public health challenge, because there are multiple factors driving vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy occurs when there is a reluctance to receive a vaccine despite its availability. Developing strategies to build trust with people from racial and ethnic minority communities and the medical community are essential to effectively promoting health.

Moving from willingness (to take a vaccine) to vaccination uptake remains a public health challenge, because there are multiple factors driving vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy occurs when there is a reluctance to receive a vaccine despite its availability. Developing strategies to build trust with people from racial and ethnic minority communities and the medical community are essential to effectively promoting health.NIMHD supports research in this area to eliminate health disparities and incorporate strategies to address:

- Social determinants of health that create barriers to accessing vaccines.

- Sustainable collaborations in communities disproportionately affected by illnesses.

NIMHD continues to invest in community-engaged research among populations experiencing health disparities to promote wellness and protect health through vaccines. We held an NIH extramurally funded grantee meeting on COVID-19 vaccine uptake in 2022 where several insights were shared. In this blog post, we share these insights and a brief overview of how applying knowledge, steadfastness, and collaboration can help promote vaccine uptake. While we know some people are reluctant and may be unsure about being vaccinated, hopefully this blog will help to inform them.

What are the benefits of vaccines?

Vaccines provide multiple benefits for the prevention or reduction of disease, serious illness, or death while also protecting against disease transmission. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends vaccinations across the lifespan for protection against many diseases.

For example, influenza or the flu is an infection of the respiratory system that can cause serious complications for children ages 2 or younger, pregnant people, adults over age 65, and people with chronic health conditions. The flu causes more than 400,000 hospital stays and 50,000 deaths each year in the United States, with the highest rates among Black and African American and American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations. Yet less than 43% of Latino and Hispanic, AI/AN, and Black and African American adults and less than 54% of Latino and Hispanic and Black and African American children receive the flu vaccine.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved vaccines are critical for reducing infection rates and slowing the spread of infectious diseases. Despite the CDC’s recommendations and the overwhelming benefits of vaccination, disparities exist in the acceptance and uptake of vaccines (e.g., COVID-19, flu, pneumococcal, hepatitis B, pertussis, measles, and human papilloma virus) among populations experiencing health disparities. These disparities also occur for many routine immunizations for all ages.

What drives vaccine hesitancy?

The COVID-19 pandemic showed us that vaccine hesitancy is complex; context specific; and changes across time, place, and type of vaccine, as well as in the timely completion of a vaccine series (i.e., receiving all vaccines within a series). It can also be influenced by factors such as complacency, convenience, and confidence.

Pathways of vaccine hesitancy vary and are subject to change over time. For instance, parental vaccine hesitancy for childhood vaccines is growing within the United States for diseases such as measles, despite measles being declared eliminated in the United States in 2000 due to a prior robust vaccination program.

Racial and ethnic minority populations may be more likely to experience skepticism about the trustworthiness of the source(s) of vaccination recommendations due to prior experiences of marginalization and mistreatment within the medical community. Cultural and religious factors may also influence vaccine uptake and low risk perceptions of disease.

Other factors such as limited knowledge, limited information on vaccines, concerns about perceived safety, parental perceptions of vaccine safety, public uncertainty, low health literacy, considering immunization a low priority, and exposure to misinformation or disinformation via social media channels play a role in vaccine uptake.

Getting protected: What you need to know

Winter months are critical times for vaccines, especially COVID-19, flu, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). People may also be behind on other vaccines due to health care closures and accessibility issues during COVID-19. So how can we encourage the people around us to get vaccinated? Community-based organizations and health care providers can do the following:

- Engage others in meaningful, authentic communication when you discuss vaccines.

- Identify and address the needs, preferences, and concerns of a group in discussions about vaccines.

- Provide targeted messaging that meets people where they are, in terms of their decision to vaccinate and the places where they receive care.

- Give understandable communication that comes from a trusted source (e.g., health care provider or community leader).

- Provide different modalities for messaging about vaccines (e.g., text message, face-to-face interactions, social media, videos).

These strategies can be helpful to increase vaccine uptake within your community. In addition to getting vaccinated, please continue to use evidence-based mitigation strategies to reduce the risk of spreading infectious diseases, such as mask wearing and frequent hand washing. Persistence to these strategies and drawing on community-based collaborations can help promote health among populations experiencing health disparities.

On-going NIMHD vaccine related funding opportunities and initiatives:

- NOT-MD-23-008: Notice of Special Interest: Research to Address Vaccine Uptake and Implementation Among Populations Experiencing Health Disparities

- Approved Funding Concept: Multilevel Pathways and Interventions to Promote Vaccine Uptake Among Populations Experiencing Health Disparities

Want to know more about how NIH is addressing vaccine hesitancy, uptake, and implementation among populations experiencing health disparities in the United States and its territories?

- NIH Community Engagement Alliance (CEAL): CEAL Against COVID-19 Disparities works closely with the communities hit hardest by COVID-19.

- RADx® Underserved Populations (RADx-UP) was created by NIH to ensure that all Americans have access to COVID-19 testing, with a focus on communities most affected by the pandemic.

To locate vaccines near you: www.vaccines.gov

Deborah Linares, Ph.D., M.A., is a Health Scientist Administrator (Program Official) at NIMHD. She focuses on promoting research to understand behavioral and interpersonal factors contributing to resilience and susceptibility to adverse health conditions among disadvantaged and underserved populations. She provides expertise in conducting minority health and health disparities research in the areas of behavioral health, women’s health, child development, healthy aging, eHealth, and cancer control.

Vanessa Marshall, Ph.D., is a Social Behavioral Scientist Administrator (Program Officer) in the Division of Community Health and Population Science at NIMHD. She manages and conducts research to advance public health prevention science. Her research focuses on improving health outcomes and promoting research to understand and address the multilevel determinants of factors that play a role in health disparities. She provides expertise in key research areas including minority health, health disparities, health services research, community engaged research, clinical trials, public health, quality improvement, implementation, dissemination and evaluation.

-

New Policy Paves Way to Scientific Discovery in a Data-Rich World

By Paul Cotton, Ph.D., RDN

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

Posted Feb. 27, 2024Insights Into the 2023 NIH Data Management and Sharing Policy

In a significant development for the scientific community, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) unveiled its Data Management and Sharing (DMS) policy. The DMS policy represents a major step forward in promoting transparency, reproducibility, and collaboration within the realm of biomedical research. By emphasizing responsible and efficient sharing of research data, the NIH aims to maximize the impact of its investments and foster scientific discoveries that benefit society at large. This blog post explores the key elements and implications of the NIH's groundbreaking policy.

In a significant development for the scientific community, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) unveiled its Data Management and Sharing (DMS) policy. The DMS policy represents a major step forward in promoting transparency, reproducibility, and collaboration within the realm of biomedical research. By emphasizing responsible and efficient sharing of research data, the NIH aims to maximize the impact of its investments and foster scientific discoveries that benefit society at large. This blog post explores the key elements and implications of the NIH's groundbreaking policy.Enhancing Data Management Practices

The DMS policy places a strong emphasis on robust data management practices throughout the research lifecycle, requiring grant applicants to submit a detailed Data Management and Sharing Plan (DMSP). The DMSP should outline how prospective grantees will handle, store, and share research data generated throughout the duration of NIH-funded projects and beyond. This proactive approach ensures that data management is considered an integral part of the research process from the outset, thereby minimizing the risk of data loss or mismanagement.

Promoting Data Sharing and Accessibility

One of the primary objectives of the NIH's DMS policy is to enhance data sharing and accessibility. Under the new guidelines, researchers are expected to make their data widely available to the scientific community, enabling other researchers to validate findings, conduct secondary analyses, and generate new insights. By fostering a culture of data sharing, the NIH aims to accelerate scientific progress, encourage collaborations, and avoid unnecessary duplication of efforts.

The new policy facilitates data sharing by encouraging the use of data repositories that comply with FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles. FAIR ensures that research data is easily discoverable, accessible to all interested parties, and effectively utilized across different platforms and disciplines. Moreover, the NIH requires that data be shared in a timely manner, allowing other researchers to benefit from and build upon existing knowledge.

Protecting Privacy and Confidentiality

While promoting data sharing, the NIH also recognizes the importance of protecting individual privacy and confidential information. The data management and sharing policy emphasizes the need for researchers to handle sensitive data responsibly and take appropriate measures to safeguard participant privacy. It encourages the use of de-identified data whenever possible, ensuring that personal information remains protected while still enabling valuable research insights.

Training and Compliance

Recognizing the need to support researchers in implementing the new policy, the NIH is committed to providing training, resources, and guidance on data management and sharing practices. Our commitment helps equip researchers with the necessary knowledge and skills to adhere to the policy requirements. Additionally, compliance with the new data management and sharing policy will be monitored as part of the NIH's existing grant oversight and evaluation processes.

Conclusion

The NIH's new Data Management and Sharing Policy marks a significant milestone in advancing scientific collaboration and transparency. By promoting responsible data management and sharing practices, the policy aims to accelerate scientific discoveries, maximize the impact of research investments, and ultimately improve human health. While fostering collaboration and accessibility, it also recognizes the importance of privacy protection and compliance with ethical guidelines.

The NIH's commitment to supporting researchers through training and resources underscores our dedication to facilitating the implementation of this progressive policy. Stay tuned for future posts, where we will explore specific Data Management and Sharing Policy updates, share success stories, and provide valuable insights to help you navigate the evolving landscape of grant funding. Together, let us embark on this journey of clarity and collaboration as we strive to make a lasting impact in the fields of health and research as the scientific community embraces this new era of data sharing, exciting opportunities for breakthroughs and collaborations lie ahead.

Paul Cotton, Ph.D., RDN, is the Director of NIMHD’s Office of Extramural Research Activities. He advises on and manages science policy and program activities related to extramural administrative management, scientific management, and scientific initiatives, and is responsible for the development and implementation of policies for managing research awards and overseeing research training policies, as well as supporting diversity, equity, and inclusion research initiatives.