Abstract

Background

Child sexual abuse is associated with adverse outcomes, including heightened vulnerability that may translate into risk of revictimization. The aims of the study were: (1) to explore the direct and indirect links between child sexual abuse and cyberbullying, bullying, and mental health problems and (2) to study maternal support as a potential protective factor.Methods

Teenagers involved in the two first waves of the Quebec Youths' Romantic Relationships Survey (N = 8,194 and 6,780 at Wave I and II, respectively) completed measures assessing child sexual abuse and maternal support at Wave I. Cyberbullying, bullying, and mental health problems (self-esteem, psychological distress, and suicidal ideations) were evaluated 6 months later.Results

Rates of cyberbullying in the past 6 months were twice as high in sexually abused teens compared to nonvictims both for girls (33.47 vs. 17.75%) and boys (29.62 vs. 13.29%). A moderated mediated model revealed a partial mediation effect of cyberbullying and bullying in the link between child sexual abuse and mental health. Maternal support acted as a protective factor as the conditional indirect effects of child sexual abuse on mental health via cyberbullying and bullying were reduced in cases of high maternal support.Conclusions

Results have significant relevance for prevention and intervention in highlighting the heightened vulnerability of victims of child sexual abuse to experience both bullying and cyberbullying. Maternal support may buffer the risk of developing mental health distress, suggesting that intervention programs for victimized youth may profit by fostering parent involvement.Free full text

CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE, BULLYING, CYBERBULLYING, AND MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS AMONG HIGH SCHOOLS STUDENTS: A MODERATED MEDIATED MODEL

Abstract

Child sexual abuse is associated with adverse outcomes, including heightened vulnerability that may translate into risk of revictimization. The aims of the study were: (1) to explore the direct and indirect links between child sexual abuse and cyberbullying, bullying, and mental health problems and (2) to study maternal support as a potential protective factor. Methods: Teenagers involved in the two first waves of the Quebec Youths’ Romantic Relationships Survey (N = 8,194 and 6,780 at Wave I and II, respectively) completed measures assessing child sexual abuse and maternal support at Wave I. Cyberbullying, bullying, and mental health problems (self-esteem, psychological distress, and suicidal ideations) were evaluated 6 months later. Results: Rates of cyberbullying in the past 6 months were twice as high in sexually abused teens compared to nonvictims both for girls (33.47 vs. 17.75%) and boys (29.62 vs. 13.29%). A moderated mediated model revealed a partial mediation effect of cyberbullying and bullying in the link between child sexual abuse and mental health. Maternal support acted as a protective factor as the conditional indirect effects of child sexual abuse on mental health via cyberbullying and bullying were reduced in cases of high maternal support. Conclusions: Results have significant relevance for prevention and intervention in highlighting the heightened vulnerability of victims of child sexual abuse to experience both bullying and cyberbullying. Maternal support may buffer the risk of developing mental health distress, suggesting that intervention programs for victimized youth may profit by fostering parent involvement.

INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is a key period in human development[1] during which harmful experiences can significantly influence the course of life in the long term.[2,3] Challenges associated with this crucial period may even be more salient for youth that have been confronted with adverse life events. Among these vulnerable populations are adolescents with a history of child sexual abuse. Indeed, child sexual abuse in all its forms (unwanted sexual touching, completed or attempted penetration) is one of the most difficult experiences a child or a young person may sustain.[4] Studies among youth have shown the deleterious impacts associated with sexual abuse affecting both the mental[4–7] and physical health of victims.[8]

Scholarly reports have also underscored the greater vulnerability of victims of child sexual abuse to other forms of interpersonal victimizations including sexual harassment,[9] teen dating violence,[10] and adult partner violence.[11] Yet, very few reports have explored possible links between sexual abuse and bullying and studies that have, have investigated it partially.[12, 13] In recent years, cyberbullying has garnered much interest among practitioners from education and health settings as well as researchers concerned with the high prevalence of the phenomenon and its negative impact on teenagers. Empirical reports have identified vulnerable populations of youth who are at an increased risk of experiencing cyberbullying, including sexual minority teenagers[14] and highly Internet-connected youth.[15–18] However, to our knowledge, no study has examined sexual abuse as a potential risk factor for this new and increasingly discussed form of victimization. Although studies have looked into the risk factors associated with cyberbullying and sexual abuse separately,[19–22] the association between child sexual abuse and cyberbullying remains to be explored.

Defined as an aggressive, deliberate, and repeated behavior inflicted by an individual to another through the use of computers, cell phones, and other electronic devices,[20, 21] cyberbullying appears to be frequent among adolescents. Meta-analyses identify prevalence rates varying from 20 to 40% and even up to 70% for some vulnerable groups.[21, 23] With youths’ increasingly growing access to social media, which are used in all spheres of their lives, such platforms can be used to carry out acts of intimidation and violence, even in the context of dating violence.[24] Recent studies have shown that young victims of cyberbullying present a higher level of mental health problems (psychological distress, low self-esteem, suicidal ideations) than nonvictims.[14, 25, 26]

In light of these recent findings, identifying youth at risk for cyberbullying appears warranted in order to design appropriate intervention and prevention strategies. Given that prior research has clearly shown that sexually abused youth are particularly vulnerable to later interpersonal victimization, it is important to unearth potential associations between sexual abuse and cyberbullying. However, scholars have underscored that cyberbullying should not be analyzed without simultaneously considering “traditional” bullying experiences occurring in the “real world.”[27]

To orient intervention, it is also important to identify potential protective factors that may help break the cycle of revictimization. Studies conducted with youth victims of sexual abuse have shown considerable diversity of mental health outcomes in survivors and a number of factors have been put forward to explain this diversity. Among these factors is support from the nonoffending parent (the mother in the majority of cases), which has been identified as playing a crucial role influencing outcomes in survivors as well as their capacity to cope with later adverse life events or potentially abusive situations.[28] Thus, maternal support may buffer psychological distress associated with trauma. Yet, authors have argued that perceived support may promote well being particularly for individuals under stress.[29] Therefore, it is of interest to investigate potential interactions that can highlight whether maternal support is more important for victims of child sexual abuse as compared to nonvictims.

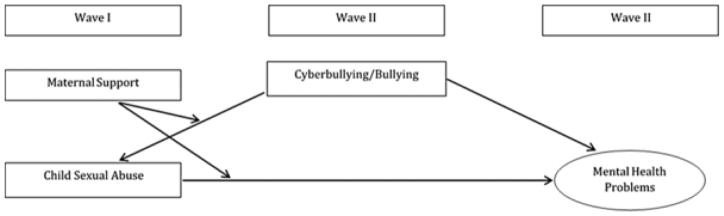

Using data from the Quebec Youths’ Romantic Relationships Survey (QYRRS), the present study aims to study the association between sexual abuse and cyberbullying among a large representative sample of youth and to explore the potential direct and indirect effects of sexual abuse on cyberbullying, and indicators of mental health. The potential protective function of maternal support will also be explored. To address critics of past studies, traditional bullying will also be integrated in the model to be tested. Figure 1 illustrates the tested model. We hypothesized that: (1) child sexual abuse will be positively associated with cyberbullying and bullying; (2) the association between child sexual abuse and mental health indicators will be mediated by cyberbullying and bullying; and (3) maternal support will act as a significant moderator between sexual abuse and (a) cyberbullying and bullying, and (b) mental health problems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SAMPLE

We used data from the first and second waves of the QYRRS primarily aimed at documenting the prevalence of dating violence, exploring associated risk factors and mental health outcomes in high school adolescents aged 14–18 years.

The target population of the survey included all students in grades 10–12 (youth sector, aged 14–18 years) attending public and private schools in Quebec. The first wave of the survey was completed through a one-stage stratified cluster sampling of high schools in 2011–2012. Schools were randomly selected from an eligible pool from the Quebec Ministry of Education for the 2010–2011 school year. As schools in the whole population are stratified according to metropolitan geographical area, status of schools (public or private schools), teaching language (French or English), and social economic deprivation index, surveyed schools were classified into eight strata giving the aforementioned characteristics in order to obtain a representative sample of students in grades 10–12. In all, 34 high schools participated.

Within the same school, students in the three grades were invited to participate in the study without any restriction. Class response rates and the overall student response rate were determined as the ratio between the number of students that accepted to participate (students from whom written consent was obtained) and the number of solicited students. Response rate was 100% for the majority (320 out of 329) of classes; whereas for the remaining, the response rate ranged from 90 to 98%. Overall, 99% of the students agreed to participate. The rate of partial nonresponse was less than 3.5% for the majority of variables and no additional adjustment was made for nonresponse as bias and loss of power are likely to be inconsequential.

Participants at Wave I were given a sample weight to correct biases in the nonproportionality of the schools sample compared to the target population. The weight was defined as the inverse of the probability of selecting the given grade in the respondent’s stratum in the sample multiplied by the probability of selecting the same grade in the same stratum in the population. A weighted sample of 6,531 youths resulted and is used in further analyses. Students agreed to participate on a voluntary basis and signed a written consent form. The institutional review board of the Université du Québec à Montréal approved this study.

At Wave I, questionnaires were completed by 8,194 students. Six months later, students in the same schools were asked to participate in Wave II. Six thousand seven hundred and eighty teens completed the questionnaire. Sample characteristics at Wave 1 were as follows: 57.8% of participants were girls. Although 63.2% of participants reported living with both parents, 34.6% lived either in single-parent families or in shared custody and 2.2% described another living arrangement (living in foster care, with a member of the extended family). Respondents were mostly French speaking. A total of 75.4% reported speaking only French at home, 3.6% only English, 5.1% both French and English, and 15.9% other languages.

MEASURES

Sexual abuse and maternal support were completed at Wave I, whereas cyberbullying, bullying, and mental health indicators were derived from Wave II, conducted on the average 6 months later.

Lifetime Child Sexual Abuse

Two items were adapted from previous studies to assess sexual abuse.[30, 31] One item referred to unwanted touching (Have you ever been touched sexually when you did not want to, or have you ever been manipulated, blackmailed, or physically forced to touch sexually) and one item refered to unwanted sexual activities involving penetration (Has anyone ever used manipulation, blackmail, or physical force, to force or obligate you to have sex [including all sexual activities involving oral, vaginal, or anal penetration]?) A dichotomized score was created based on the absence (0) or presence (1) of child sexual abuse.

Maternal Support

The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA) questionnaire was used to assess the participant’s relationship with their mother at Wave 1.[32] The three questions (e.g., My mother cares about me) are on a five-point Likert scale ranging from Never (0) to very often (4). The questionnaire showed good reliability (Cronbach α = 0.83). A subscore was computed based on the mean of the three items, which was then multiplied by 3. The support score ranged from 0 to 12.

Cyberbullying and Bullying

These were measured at Wave 2, covering the 6-month window between Waves 1 and 2, using one question each “How many times did someone harass you (with rumors, intimidation, threats, etc.) electronically (Facebook, MySpace, MSN, emails, texts, etc.)” and “How many times did someone harass you (with rumours, intimidation, threats, etc.) at school or elsewhere (excluding electronically)?” Respondents rated on a four-point scale: Never (0), 1–2 times (1), 3–5 times (2), and 6 times and more (3).

Mental Health Indicators

Three indicators were evaluated at Wave 2: self-esteem, psychological distress, and suicidal ideation. The short version of Self-Description Questionnaire including four items was used to assess the participants’ self-esteem.[33] Responses of this scale range from 0 (false) to 4 (true) resulting in a score varying from 0 to 16 (α = .90). Following past studies, a clinical cutoff point of 10 or less was used to define low self-esteem.[34] Suicidal ideations were assessed using a single question: “In the last 6 months, have you ever seriously thought of committing suicide?” Participants responded Yes (1) or No (0). The 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale assessed psychological distress over the past week.[35] Items were on a five-point scale: 0 (never) to 4 (always), with a total score ranging from 0 to 40 (α = .90). A score of 9 and higher was used to identify clinical psychological distress.[36]

Socio-Demographic Variables

Information was collected on sex, age, family structure (living with both parents in the same household, living with both parents in different households—shared custody, living with one parent, other family structure arrangements), main language spoken at home (French, English, or other), and ethnicity of parents.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Prevalence of each variable was computed and differences between genders were tested. For categorical variables, the Pearson χ2 statistic is corrected for the survey design with the second-order correction of Rao and Scott[37, 38] and is converted into an F (Fisher) statistic; thus, an F statistic is reported for difference between categorical indicators. A latent variable was derived to describe mental health problems including self-esteem, psychological distress, and suicidal ideation. This latent variable was included in the model used to assess a moderated mediated model based on Preacher et al.’s approach.[39] Such model allows us to test (1) the association between (a) child sexual abuse and cyberbullying, and (b) child sexual abuse and bullying; (2) the association between both sexual abuse and cyberbullying/bullying, and mental health indicators; and (3) the moderated effect of maternal support on the relationship between sexual abuse and (a) cyberbullying/bullying, and (b) mental health indicators (Fig. 1). An interaction between sexual abuse and maternal support was added in the model to estimate the moderator effect.[39, 40] Covariates included sex and age of participants. Analyses were conducted using Stata 13[41] and Mplus 6.[42]

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE AND BIVARIATE ANALYSES

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive analyses. Overall, 17.47% of youth reported being victims of cyberbullying in the past 6 months. Girls (19.83%) presented significantly higher prevalence of cyberbullying than boys (13.84%; F (1, 25) = 10.64; P = .0032). The person involved was mainly described as another youth (91.54%), an adult (5.54%) or both a teen and an adult (2.92%). Girls and boys reported similar rates of bullying (20.06% for girls and 17.89% for boys; F (1, 25) = 1.32; P = .2621). Participants reported the person involved in bullying was another youth (94%), an adult (4.40%), or both a youth and adult (1.60%). Overall, of students reporting being exposed to cyberbullying in the past 6 months, 54.03% had also been bullied. About half (49.15%) of teenagers reporting bullying reported experiencing at least one episode of cyberbullying in the past 6 months. Girls were more likely than boys to report having experienced child sexual abuse (F (1, 26) = 108.31; P < .001) and to report clinical psychological distress (F (1, 25) = 206.31; P < .001), suicidal ideations (F (1, 26) = 12.18; P < .001), and low self-esteem (F (1, 26) = 41.08; P < .001). Overall, girls reported higher scores (10.16 ± 0.10) of maternal support than boys (9.85 ± 0.06), (F (1, 26) = 9.88; P = .004).

Table 1

Descriptive of main variables

| Measures | Girls | Boys | F2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child sexual abuse (%) | 14.89 | 3.94 | 108.31 | <.001 |

| Bullying (%) | 20.06 | 17.89 | 1.32 | .2621 |

| Cyberbullying (%) | 19.83 | 13.84 | 10.64 | .0032 |

| Maternal support (mean) | 10.16 | 9.85 | 9.88 | .004 |

| Mental health problems | ||||

Psychological distress (%) Psychological distress (%) | 46.47 | 22.25 | 206.31 | <.001 |

Low self-esteem (%) Low self-esteem (%) | 41.08 | 23.32 | 94.41 | <.001 |

Suicidal ideations (%) Suicidal ideations (%) | 12.18 | 4.80 | 78.42 | <.001 |

Bivariate analyses revealed that child sexual abuse was associated with cyberbullying. Results revealed that 33.47% of sexually abused girls reported experiencing cyberbullying compared to 17.75% of nonsexually abused girls (F (1, 25) = 50.56; P < .001). Similar results were found for boys; the rate of cyberbullying was found to be 29.62% for sexually abused boys and 13.29% for nonsexually abused boys (F (1, 22) = 33.68; P < .001). We observed the same pattern for bullying. Both sexually abused girls (33.88%) and boys (34.71%) were found more likely to experience bullying (excluding electronically) compared to teenagers without a history of child sexual abuse (17.86 and 17.21% of nonsexually abused girls and boys, respectively; F (1, 25) = 44.23; P < .001 for girls and F (1, 22) = 12.20; P = .002 for boys).

MODERATED MEDIATED ANALYSES

Results of the moderated mediated model are presented in Table 2, and main effects are illustrated in Fig. 2. As hypothesized, cyberbullying was significantly associated with child sexual abuse (β = 0.40; P < .001) as well as maternal support (β = −0.08; P < .001), sex (β = 0.12; P = .009), and age (β = −0.06; P = .012). Younger participants, those with a history of child sexual abuse, and those reporting less maternal support were found more likely to experience cyberbullying (Table 2). The interaction between child sexual abuse and maternal support did not reach significance. Child sexual abuse (β = 0.36; P < .001), as well as maternal support (β = −0.09; P < .001) and age (β = −0.07; P < .001) were significantly associated with “traditional” bullying. Younger participants, those with a history of child sexual abuse, and those reporting less maternal support were found more likely to report experiencing “traditional” bullying in the past 6 months. The interaction term was not significant.

Results of moderated mediated model between sexual abuse, cyberbullying, bullying, maternal support, and mental health problems.

TABLE 2

Results of moderated mediated model

| Cyberbullying | β | T | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

Child sexual abuse Child sexual abuse | 0.40 | 6.32 | <.001 |

Maternal support Maternal support | −0.08 | −5.25 | <.001 |

Maternal support* Child sexual abuse Maternal support* Child sexual abuse | −0.13 | −1.81 | .071 |

Sex Sex | 0.12 | 2.59 | .009 |

Age Age | −0.06 | −2.53 | .012 |

|

| |||

| Bullying | |||

Child sexual abuse Child sexual abuse | 0.36 | 4.68 | <.001 |

Maternal support Maternal support | −0.09 | −5.57 | <.001 |

Maternal support* Child sexual abuse Maternal support* Child sexual abuse | −0.07 | −1.43 | .153 |

Sex Sex | 0.02 | 0.39 | .696 |

Age Age | −0.07 | −4.11 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Mental health problems | |||

Cyberbullying Cyberbullying | 0.29 | 7.38 | <.001 |

Bullying Bullying | 0.37 | 6.94 | <.001 |

Child sexual abuse Child sexual abuse | 0.72 | 4.56 | <.001 |

Maternal support Maternal support | −0.47 | −11.06 | <.001 |

Maternal support* Child sexual abuse Maternal support* Child sexual abuse | 0.01 | 0.60 | .952 |

Sex Sex | 1.43 | 11.41 | <.001 |

Age Age | −0.03 | −0.48 | .63 |

Mental health problems (i.e., suicidal ideations, psychological distress, and low self-esteem) were significantly associated with both cyberbullying and bullying, child sexual abuse, sex, and maternal support (Fig. 2). The direct effect of sexual abuse on mental health problems was significant (β = 0.72; P < .001). Results also revealed an indirect effect through cyberbullying (β = 0.12; P < .001) and another one via bullying (β = 0.13; P < .001). This suggests a partial mediation effect of cyberbullying and bullying in the relationship between child sexual abuse and mental health problems. The overall model explained 31.2% of the variance in mental health problems. Although the interaction term failed to reach significance, the conditional effect of sexual abuse on mental health problems through cyberbullying and bullying was found to decrease as perceived maternal support increased (Table 3).

TABLE 3

Conditional indirect effect of child sexual abuse on mental health problems through cyberbullying and bullying

| Maternal support | Effect | Z | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyberbullying | |||

Low maternal support Low maternal support | 0.15 | 4.87 | <.001 |

Mean maternal support Mean maternal support | 0.11 | 4.67 | <.001 |

High maternal support High maternal support | 0.08 | 2.43 | .015 |

| Bullying | |||

Low maternal support Low maternal support | 0.17 | 3.87 | <.001 |

Mean maternal support Mean maternal support | 0.13 | 3.72 | <.001 |

High maternal support High maternal support | 0.10 | 2.23 | .025 |

Z, standard normal statistics.

Low maternal support: Mean − 1 Standard deviation; High maternal support: Mean + 1 Standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed the association between child sexual abuse and cyberbullying with a large representative sample of high school youth from Quebec (Canada), and explored potential direct and indirect effects of child sexual abuse, maternal support on cyberbullying and “traditional” bullying, and indicators of mental health problems. Results of this study show that cyberbullying is a major concern that affects a significant proportion of teenagers, in particular those who are more vulnerable, namely victims of child sexual abuse.

First, our results found girls to be more vulnerable to being victims of cyberbullying, which corroborates with past studies. However, prevalence rates of cyberbullying in teenage girls and boys and the identification of gender differences vary depending on empirical reports, especially according to the different forms of cyberbullying studied.[20] That said, recent studies suggest not only that girls are more likely to be victims of cyberbullying than boys, but that they may also present higher perpetration rates.[43]

Second, we examined the relation between sexual abuse and cyberbullying. Twice as many sexually abused girls experienced cyberbullying (33.47%) compared to nonsexually abused girls (17.75%). The same observation is noted for boys (29.62 vs. 13.29%). Then, direct and positive association links were observed between sexual abuse and cyberbullying. These results can be explained by the fact that sexually abused youth are more likely to experience subsequent sexual, psychological, and physical victimization, whether it be in the context of romantic relationships or other types of interpersonal relationships.[44, 45] Indeed, past studies have shown that the aftermath of sexual abuse may translate into a sense of betrayal, shame, stigmatization, associated with significant impact on interpersonal functioning (boundary issues in relating to others, greater mistrust, difficulties in self-assertion),[46, 47] which in turn may lead to increased vulnerability to revictimization.

Findings of this study also showed that sexually abused youth as well as victims of cyberbullying present higher levels of mental health problems (i.e., psychological distress, low self-esteem, and suicidal ideations). Cyberbullying as well as bullying in school was found to partially mediate the link between sexual abuse and negative outcomes, suggesting that revictimization is part of the explanation as to why sexual abuse translates into significant distress. The accumulation of traumatic events and adverse experience or polyvictimization is now clearly recognized as a potent risk factor for mental health symptoms.[48]

Even if our analyses failed to detect a significant interaction between child sexual abuse and maternal support, our findings of the conditional indirect effect showed that maternal support plays an important role in reducing the risk of mental health distress among sexual abuse victims. Maternal support is a protective factor that could not only reduces the risk of revictimization for young victims of sexual abuse, but also tempers the adverse consequences and potential sequelae. Results also demonstrated that greater maternal support is associated with lower mental health problems such as psychological distress, low self-esteem, and suicidal ideations. A number of studies have shown the protective effect of maternal support,[49, 50] which is a key factor in fostering recovery in sexual abuse victims. These results can be explained by the fact that the support of the nonabusive mother (primary attachment figure) can help youth develop a secure attachment form. In turn, it would reinforce the development of cognitive, personal, and social skills in order to cope with the trauma and also help them find a safe person in whom they could confide in more easily. Having such a support system in place could promote self-assertiveness and, ultimately, the avoidance of situations of revictimization.

The present study has certain limitations that must be considered. The first limitation of this study is related to the partial overlap between the mental health and cyber/bullying measures. It is possible that victims had already been struggling with mental health problems before the victimization ever took place. Future studies will need to consider other sources of support that may act as moderators, namely peer support, which increases in importance during adolescence. In addition, a more comprehensive measure of cyberbullying that also considers the involvement in cyberbullying may unearth specificities in the relationships identified.

Besides these limitations, findings of this study explored the association between child sexual abuse and bullying in school and cyberbullying, which is increasingly present in youth. Mediation and moderation analyses performed in this study provided a better understanding of the association between the variables and elucidated the subjective and complex dimensions of bullying, sexual abuse victimization, maternal support, and mental health outcomes. Analyzing cyberbullying distinctively from bullying not involving electronic devices represents a strength as cyberbullying may overlap with other forms of bullying experienced face-to-face. Findings reveal that child sexual abuse is a significant risk factor for youth to experience cyberbullying. Furthermore, results show the important protective role played by maternal support in reducing psychological distress for young victims of child sexual abuse who may experience bullying and cyberbullying.

CONCLUSION

In sum, our study attests that cyberbullying is prevalent in adolescence and associated with significant mental health problems. As several authors have previously argued, the implementation of prevention initiatives are essential. Our results highlight the heightened vulnerability of both girls and boys who have been victims of sexual abuse to experience cyberbullying. Fortunately, maternal support appears to be a protective factor that may act as buffer for negative outcomes and reduce the risk of revictimization for these vulnerable youth. These results indicate that intervention programs for youth victims of sexual abuse that foster the involvement of nonabusive mothers are likely to consolidate long-term gains and reduce the risk of revictimization. Finally, this article also points to a future avenue of research to study the contribution of maternal support into the process of developing resilient abilities among sexually abused youth and cyberbullying victims.

References

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1002/da.22504

Article citations

Why individuals with trait anger and revenge motivation are more likely to engage in cyberbullying perpetration? The online disinhibition effect.

Front Public Health, 13:1496965, 28 Jan 2025

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39935884 | PMCID: PMC11810742

The mediating effects of school bullying victimization in the relationship between childhood trauma and NSSI among adolescents with mood disorders.

BMC Pediatr, 24(1):524, 13 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39138576 | PMCID: PMC11321121

Sexual Victimization and Sexually Transmitted Infections Among a Nationally Representative Sample of Adolescents and Young Adults in Haiti.

Arch Sex Behav, 53(9):3557-3571, 05 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38969799

Depression and suicidal ideation among Black individuals in Canada: mediating role of traumatic life events and moderating role of racial microaggressions and internalized racism.

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 59(11):1975-1984, 01 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38429537

The role of child maltreatment and adolescent victimization in predicting adolescent psychopathology and problematic substance use.

Child Abuse Negl, 146:106454, 21 Sep 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37741073 | PMCID: PMC10872623

Go to all (33) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Correlates of bullying in Quebec high school students: The vulnerability of sexual-minority youth.

J Affect Disord, 183:315-321, 15 May 2015

Cited by: 25 articles | PMID: 26047959 | PMCID: PMC4641744

Evaluating Risk and Protective Factors for Suicidality and Self-Harm in Australian Adolescents With Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimizations.

Am J Health Promot, 36(1):73-83, 26 Jul 2021

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 34308672

The potential role of subjective wellbeing and gender in the relationship between bullying or cyberbullying and suicidal ideation.

Psychiatry Res, 270:595-601, 19 Oct 2018

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 30384277

Cyberbullying: Review of an Old Problem Gone Viral.

J Adolesc Health, 57(1):10-18, 01 Jul 2015

Cited by: 95 articles | PMID: 26095405

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (1)

Grant ID: 103944-1